CACAO - The World Tree and Her Planetary Mission

By Jonathon Miller Weisberger

How can a relatively inconspicuous understory treelet be so pregnant with wholesome goodness, so full of virtues, and so charged with mythologies? Why is cacao revered so much that it has been used as money, as medicine, as food, as incense, and for ceremonial offerings on a vast array of occasions—to invoke responses from supernal beings; to celebrate special moments, holidays and calendar markers such as the solstice and equinox; to sanctify weddings and births; to consecrate times of initiations and rites of passage; and as funeral offerings to accompany the dead on the afterlife voyage?

When we stretch our imagination to contemplate ancient creation myths that consider cacao not just a gift from the gods to humanity, but an actual component of our identity as humans, we can begin to understand. The Popol Vuh, the Quiché Mayan holy book, asserts that the gods created humans from Maize and Cacao, along with other staple foods such as Pataxte, Zapote, Jocote, Nance, and Matasano. Many other creation myths of Central American peoples postulate human origins in Cacao. And depictions are found on ancient pottery of the Maya great mother Ix Chel, lady of translucent rainbow light, goddess of medicine, weaving, fertility, and the crescent moon, exchanging Cacao with the rain god Chac, who is the patron of agriculture. This iconography is rooted in the tree’s reputation for acting as a conduit for communion with supernatural realms, as a medium between heaven and earth. To the ancient peoples who grew and adored Cacao, this sacred crop was a Tree of Life uniting the natural world and the spirit world. The offering of Cacao, through ritual imbibition, ceremony and song, functioned to symbolically connect individuals with the powers that govern their existence, with renewal and rebirth, and with the deities of creation. The bounty of the Cacao tree in Mesoamerica also created a metaphorical link to abundance, and her rounded fruit was a symbol for fertility. The deep spiritual meaning of Cacao crystalized her importance in all pre-Colombian societies that knew her. Cacao is a blessed and scrumptious elixir that has shaped and formed societies, igniting creation and urging us to evolve.

Don Memo Morales, an elder of the Costa Rican Brunka tribe, once shared a story with me. “After the cataclysm, when the earth was burned by fire, heaven had compassion for humanity, and from the sky dropped seeds of Cacao. From these seeds grew the Cacao tree, and from its ripe pregnant fruit was born the first woman, who gave birth to the first man, and from there the first people came.” Softly, Memo continued, “In compassion for humanity, the Creator gave the first people three types of Cacao so they could live well: a sweet variety to share and to enjoy in festivals, a simple variety to eat every day as food, and a bitter variety for healing all illness.”

Cacao is the incarnation of heaven’s compassion for humanity, helping us rise above the lowly state humans so easily fall back into and be closer to the divine realms. She represents the story of humanity’s constant state of evolution. She advocates harmony in all our relationships. She invigorates us to rise up, to strive with all our might, fury, and passion to achieve a heavenly way, one that is rooted in respect for all creation. She also whispers a subtle warning that if we don’t evolve, if we don’t change, we risk certain catastrophe. She could be the messenger of yet another apocalypse. She has witnessed the rise and fall of many societies.

Cacao invites you to contemplate the vastly beautiful realms that she represents. She wants you to know where she comes from, for she is a representative of the most species-rich and wettest terrestrial biome. She represents a diverse, vastly intricate and complex union of thousands of species of plants, animals, insects, birds, fungi, a dazzling array of life forms. She wants you to know about the marvelous existence of the pinnacle of terrestrial biological diversity, the tropical rainforest. She wants you to see rivers gushing, crystal-clear and clean, and gurgling springs surrounded by green. She wants nature to live uninhibited and wildlife to be happy. She also wants you to know about the sun, and how its selfless warmth represents the deeper truer heart within your heart, your true heart that is selfless and universal. She wants you to know how to embody a harmonious balance between the fire energies of your mind and the water energies of your body, through cultivating a firm body and strong and activated heart center. She wants you to know about ice-capped mountains – everlasting beacons – and an eastern range that drops down to foothills, a place known as the eyebrows of the Andes, on whose slopes Cacao evolved. She wants you to be holy and firm like the mountains she comes from, so you may be healed, so you may be integrated in body, mind, and spirit, so you may be wholesome and strong. This is the heart and the mind of Cacao.

She Has Come a Long Way and She Has a Long Way to Go

Today there is undeniable evidence that Cacao originally comes from the upper Amazon, from the base of the Andes in modern day Ecuador, in South America. How she made it into Central America is unknown. She was carried north, perhaps by nonhuman mammals, or perhaps by traders among the ancient humans. If we look at the first option, we know that the isthmus of Panama rose out of the sea between 3 and 7 million years ago, opening the land bridge between Central and South America. After that, Cacao may have been steadily moved around by monkeys, rodents, and other mammals who adore its sweet pulp but leave behind the bitter seeds, slowly spreading west, north, east and south.

Studies by geneticist Omar E. Cornejo demonstrate that the oldest known domesticated Cacao strains in Central America originated in the Amazon. Central American peoples were cultivating strains of Cacao that had been domesticated in the upper Amazon by MayoChinchipe people thousands of years prior. We know very little about the people today called the Mayo-Chinchipe, who had an elaborate and ceremonial culture that spanned a period of over 4000 years and who lived at the base of the Andes, along the equator, in the wettest and most biologically diverse part of the planet. At the Santa Ana - La Florida archeological site in southeastern Ecuador, Claire Lanaud and Rey Loor dated residues found in elaborate stone and pottery vessels as far back as 5500 years. These studies reveal the oldest-known evidence of Cacao use. Based on the finding of Spondylus and Strombus shells at La Florida, we know there was trade between the Mayo-Chinchipe and costal societies. Coastal peoples of ancient America were navigators and avid wanderers, who traded knowledge and goods such as plant materials, gold work, and jade carvings up and down the Pacific coastline. Recent studies by Smithsonian archeologists of pottery vessels on display at the National Museum of the American Indian have discovered that Cacao was consumed as far north as the Pueblo Bonito site in the Chaco Canyon of New Mexico. She sure knows how to get around.

In Central America, Olmec people began cultivating Cacao over 3800 years ago. The Olmecs’ language seems to have belonged to the Mixe-Zoque family; its word for Cacao was Kakawa, and it is at this point that that name enters history. Though far younger than the Amazonian Mayo-Chinchipe people, the Olmecs were one of the mother cultures of Mesoamerica. Their legacy is remembered primarily through the colossal stone head carvings they left behind. Few people today know of them as the Cacao connoisseurs that they were.

From the Olmecs, the Mayas learned jade carving and other skills, as well as the cultivation and use of this fascinating plant. From the Olmecs, the Mayas adopted even the name and the glyph of Cacao. The glyph shows a man’s head looking up, with a fish fin for an ear—the only difference was they accentuated the fish fin by placing yet another fin before the glyph’s main features, doubly accentuating the concept; the word “kakawa” sounds like the phrase “two fish” in Maya. Perhaps, too, the glyph for Cacao among the Olmec and Maya implies a movement upward. The fish fin represents what allows a fish to swiftly move through water, and Cacao allows a person to swiftly rise. Interestingly, the Olmecs chose the fish fin, symbolic of Cacao’s relationship to water, being she grows in the wettest regions. The Maya so adored Cacao that they officialized Cacao as a primordial element of their way of life, calling it the “World Tree” and the “First Tree.” The Maya called the beverage made from Cacao chocol’ha, from which the modern-day word “chocolate” was derived.

Today, chocolate is a common household treat. Is that her purpose? What are the implications of how we continue to consume Cacao, plaguing the planet with childhood slavery on plantations in Africa and biological extinction due to cacao plantation in northwestern South America—where are we going with this? Cacao has come a long way and she has a long way to go.

A Representative Urging us to Act on Behalf of Biological and Cultural Diversity

To understand Cacao, we must understand where she comes from. For she is an utterly symbolic representative of the pinnacle of terrestrial botanical diversity. Her origin location, along the equator, in the uppermost regions of the Amazon, is a place of balance where the day and the night are equal in length all year long, on the eastern slopes of the lush cordillera real oriental, the royal eastern ridge of the great Andes, in a gentle sloping valley, between two sacred mountains, Sumaco – known locally as the most beautiful mountain – and NapoGaleras, an isolated limestone mountain considered especially sacred by the region’s diverse indigenous peoples. Where the creases in the mountains’ foothills have acquired the curved shape of a human eyebrow, one finds the highest concentration of plant species and the richest diversity of terrestrial ecosystem types known anywhere. No other region in the world surpasses northwest South America in biodiversity, which peaks here in the “eyebrows” of the Andes. Proof of this claim is found when one compares the species counts of the tropical regions in the Americas to those of other tropical regions. Studies by the Missouri Botanical Gardens indicate that tropical Africa, including Madagascar, has 30,000 species of plants; Indonesia and Malaysia combined have 35,000; and the New World tropics have a disproportionate 90,000 species of plants. Ecuador alone has an astonishing 35,000. Cacao is born from, and rightfully represents this wondrous coexistence.

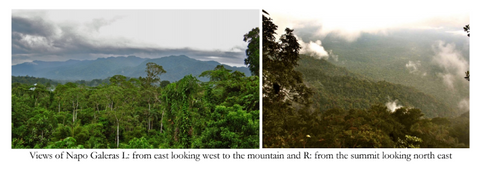

In 2010, my mentor, the botanist Dr. Carlos Cerón, and I arranged an expedition to explore the tropical wet forest on the eastern slopes of Napo-Galeras. I had previously devoted four years of sustained efforts between 1990 and 1994 to have Galeras included into the Sumaco Napo-Galeras National Park, which was being formed at that time. In 2010, thanks to the masterful knowledge of Dr. Cerón, we made a most impressive discovery.

Theobroma cacao is a member of the Malvaceae family. This is also the family that the Cotton bush and the mighty Ceiba tree belong to. On Napo-Galeras, Dr. Cerón observed a very high concentration of plant species closely related to Cacao. We encountered not only wild Theobroma cacao trees, but many other closely related species, such as Theobroma bicolor, known as patas, or cacao blanco – a white Cacao whose edible seeds are used to make chili sauce; as well as Theobroma subincanum, called cushillu cambiac, with delicious edible fruits; and the famedTheobroma grandiflorum, called cupuassu in Brasil, similarly prized for its edible fruits. We also encountered many species of Herrania, a close cousin of Cacao, such as Herrania balaensis and Herrania nitida, locally known as cambiac. These have a fine, sweet fruits, and saturated maroon flowers with remarkably elongated petal-appendages. We found other related species such asMatisia soegengii, with an edible fruit called sapote, and other species of Matisia. We encountered species in the genus Quararibea, also known as sapote. Many other related species without edible fruits grow here as well. One outstanding feature of this forest, Dr. Cerón indicated, was that here Sterculia apeibophylla, a Cacao relative, that grows usually in swampy areas in the low land Amazon, was growing on firm soil, something remarkably he had never seen elsewhere. We also found kamotoa, yet another Cacao relative, a giant emergent canopy tree that was assigned its botanical species name, Gryanthera amphibiolepis, only later, in 2012, and is vanishing due to unregulated and illegal logging.

Dr. Cerón announced to the rest of us on the expedition that this region was undeniably the origin site of Theobroma cacao, the chocolate tree, given that he had never seen such a high concentration of plants in the Malvaceae family in any other region. Coming from a master botanist, curator of the herbarium at Ecuador’s Central University, who has collected over 90,000 herbarium specimens and named dozens of species new to science, this proclamation cannot be taken lightly. He remarked that we know the origin location of plants by where there is found the highest concentration of species of a specific family. We encountered this precisely here, on the equator, at the foothills of the sacred mountain of Napo-Galeras, known in local folklore as the “End-of-the-World-Jaguar Mountain”: the origin of the chocolate tree!

A Glimpse Into Her Natural History

Many mammals disperse Cacao seeds, and many types of insects live in Cacao’s environment, but few pollinate her. Due to the evolution of Cacao’s complex floral structure, her pollinators are highly restricted to small mosquito-like insects called midges. These insects are perfectly shaped to enter and pollinate Cacao’s small bone-white flowers that appear on the tree’s trunk and branches who live in the cool moist lower level of the rainforest. Among the distributors of Cacao are most particularly monkeys, of which there are many species east of the Andes, such as the Saddleback Tamarin, a species exclusive to the tropical wet forest; the sharp-witted White-Fronted and Brown Capuchin Monkeys; the Squirrel Monkey; the graceful Woolly Monkey and elegant White-Bellied Spider Monkey. Other dispersers include tropical relatives of the Raccoon: the Kikanjou, the Bushy-Tailed Olingo, and the elusive Cacomistle that runs across the tree’s branches at night, feeding on her fruit and dispersing her seeds. Squirrels and the Tayra, a large, tree-dwelling weasel, also feasts on Cacao, as do Peccaries that manage to eat what the tree-dwellers let fall. A deeper glance into the magnificent Tropical Wet Forest ecosystem is offered in my book Rainforest Medicine, Preserving Indigenous Science and Biological Diversity in the Upper Amazon, Chapter 8, “The Eyebrows of the Andes.”

Her Cloak of Universal Wisdom

Cacao is the ultimate indicator species of the majesty of biological diversity, born from this interconnected ecosystem overflowing with abundance, an emblem of many great cultures. Yet this abundance must not be taken for granted. Without diversity, there cannot be stability, and without stability, there cannot be fertility. Indeed, without biological and cultural diversity, there cannot be an economic solution, nor an ecological nor a socio-cultural solution, to any of the modern-day dilemmas that plague humanity and the earth. As the ecologist E.O. Wilson stated in his book The Diversity of Life, “The sixth great extinction spasm of geological time is upon us, grace of mankind. Earth has at last acquired a force that can break the crucible of biodiversity.”

It is my moral obligation as a researcher in this field and ethnobotanist, granted this special opportunity to share here in The Mind of Plants, to stimulate your imagination in hopes that you will refine your gaze, sharpen your vision, and strive to see beyond the surface level of things, past the simple superficial aspects of Cacao. Given that Cacao has traveled the world over, she has evidently taken it upon herself to become a most outstanding representative for biological and cultural diversity – and this is how we must see her! This is the exhortation of Cacao: she gives but also wants us to give back; in her silent invigorating essence, she whispers a vital message: that we must return to a way of reciprocity. We must remember the source of things, and we must act on behalf of life. Cacao humbly empowers all people to rise to this occasion, to act upon injustice and suffering, for she knows that they who do not serve do not deserve to live. Born at the pinnacle of biological megadiversity, Cacao quietly and desperately holds us close to her heart with deep compassion to awaken our integral being, so we can reach the peak of consciousness: to feel the joys and sorrows of others and of nature as if they were our very own; so we can realize that what is being seen and who is seeing are one and the same; so we can learn to rise up and live in alignment with universal order; so that we can become men and women, fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters; so we can be human; so we can be real.

Then, the meditation mat of Kakawa may be revealed to us in its brilliant patterns, highlighted in orange and neon blue, with streaks of richly-saturated emerald, sapphire light swiftly blowing around all sides; and we may sit upon this mat and reflect upon the things that Kakawa teaches. We can visualize, too, the cloak of universal wisdom that the goddess of Cacao so confidently wears, orange, brown, red and yellow, engulfed in azure, cobalt and turquoise, laced with indigo and deeply rich violet, back-lit in purple. And now you, who are reading this, you, who have nibbled, sipped on and enjoyed Cacao—she wants you to wear her cloak too!

0 comments